The environment of a sailor far from shore is simple if sometimes deadly. The rules are well known and the risks understood. As long as there is sufficient sea room to run before the strength of a storm, a well found boat with a capable crew can usually survive, until they can’t. (There are storms at sea that no boat can survive and waves than can kill any ship.)

When a boat closes with the coast, things get complicated. As the sea bottom rises to meet the continental shelf, waves become steeper, herded closer together, more likely to break, sending tons of white water glissading. (A breaking wave can exert as much as one ton of pressure per square foot.) Currents can set a boat towards an unforgiving shore, poor visibility can hinder navigation, and the increased traffic increases the risk of collision. Precise positioning becomes more important—accurate charts, aids to navigations, GPS and radar help inform the situation but require expert interpretation. (The Coast Guard once used a phrase that captures the risk, radar-assisted collision.) Discrepancies between one source and another further complicate decision-making.

The once uncharted coasts of our world are littered with the bones of such self-confidence.

Imagine if you were approaching an unknown coast without accurate charts or electronic positioning, navigating by sun or stars when visible, with only hearsay about the offshore hazards or longshore currents or depth of water. The uncertainty increases exponentially. From the sailor’s perspective, the reality of the coast emerges with experience. The situation is more than just complicated, it’s complex.

There is another scenario, however. Chaos. If a storm is driving you toward a lee shore with no possibility of refuge, it doesn’t matter whether you know the soundings nearshore or your exact position. The only thing that matters is clawing your way to weather. The only thing that matters is to avoid being shattered on unyielding rocks or pounded into splintered wreckage. The only thing that matters is gaining sea room. That’s my definition of chaos.

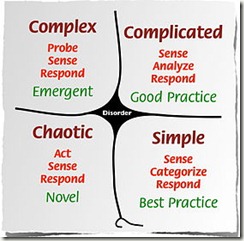

These four domains—simple, complicated, complex and chaotic—are captured in the Cynefin framework developed by David Snowden, former Director of the IBM Institute for Knowledge Management and now Chief Scientific Officer at Cognitive Edge. It’s a model to help understand the context of a situation or problem, the characteristics of that context, and the approach appropriate to that context.

Using the tools and methodology appropriate to a simple context in a complex domain is rather like sailing up to an unknown shore with naive self-confidence that intuition and past experience will be sufficient to survive. The once uncharted coasts of our world are littered with the bones of such self-confidence.

Disorder lies at the intersection of the four domains of the Cynefin framework. It’s the state of not knowing the appropriate context. I think it fair to say that is the place where we mostly live.

Despite its seeming familiarity, the world has become a different place, more complex. We have never been here before. We are all sailing toward an unknown shore, an uncharted future.